Growing Habitat and Hope for the New Year by Mary Welz, Pollinator Partnership

December 9, 2024

With the shortening of days and onset of cold temperatures, early winter is when many gardeners and growers retreat from outdoor endeavors to seek the indoor comforts of warmth and holiday cheer. While some may use this downtime to plan for what they will grow or plant in the next growing season, this time of year also offers a unique opportunity to deepen one's native plant gardening practice as well as to provide crucial habitat for pollinators and wildlife. Whether you are interested in growing potted plant material for small garden projects or have a large area for direct sowing, the dormant season is an optimal time to begin growing native plants from seed. The following guidance is offered based on my own experiences with growing native plants for various sized projects.

Species Selection

Whether you are starting a new planting project from scratch or looking to enhance existing habitat by increasing native plant diversity, there are various criteria to consider for choosing which plant species to grow:

- Choose appropriate species based on the site conditions

- Select species of plants that are native to the state or ecoregion

- Source seed locally to ensure plants are genetically adapted to local conditions

- Pick at least three species of flowering plants for each season; spring, summer, and fall

- Include native milkweeds for monarchs and native legumes for added wildlife diversity

- Don’t forget to include native grasses, sedges, and/or rushes

- Also consider adding native vines, shrubs, and trees to your planting project

- Prioritize keystone native plants to support the most species of pollinators and other wildlife

Spring- Ohio spiderwort (Tradescantia ohiensis) visited by a margined calligrapher (Toxomerus marginatus) hover fly by Mary Welz

Summer- Common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) visited by an Eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) and Western honey bees (Apis mellifera)

Fall – Common sneezeweed (Helenium autumnale) visited by golden solider beetles (Chauliognathus pensylvanicus) and a species of sweat bee (Halictus sp.)

Keystone Native Plants

Keystone native plants are essential species due to the large amount of biodiversity they support within a given ecological community in which they naturally occur. It is estimated that 90% of herbivorous insects (those that eat plants) are adapted to feed upon one or more species of closely related plants with which they have co-evolved. Research by Doug Tallamy, Desirée Narango, and their team at the University of Delaware, reveals that 14% of native plants support 90% of butterfly and moth species (collectively known as lepidoptera) in the United States. According to data compiled by pollinator conservationist Jarrod Fowler, roughly 30% of our native bee species in the US are pollen specialists, and less than half of our native plant diversity is able to serve as host plants to these at-risk pollinators. The following collection of keystone native plants supports the greatest number of larval host specific lepidoptera, pollen specialized bees, as well as a diversity of generalist pollinators.

Spring flowers of willow (Salix sp.) visited by a cellophane bee (Colletes sp.) by Amber Barnes

Stiff goldenrod (Solidago rigida) being visited by monarch (Danaus plexippus) and painted lady (Vanessa cardui) butterflies by Elizzabeth Kaufman

Keystone Native Wildflowers

- Goldenrod (genera Euthamia, Oligoneuron, Solidago)

- Aster (genera Doellingeria, Eurybia, Symphytrichum)

- Sunflower (genera Helianthus & Heliopsis)

- Joe Pye Weed & Boneset (genus Eupatorium)

- Violet (genus Viola)

- Geranium (genus Geranium)

- Black-eyed Susan (genus Rudbeckia)

- Wingstem (genus Verbesina)

- Primrose (genus Oenothera)

- Tickseed (genera Bidens & Coreopsis)

Keystone Native Flowering Trees & Shrubs:

- Willow (genus Salix)

- Blueberry, Huckleberry, etc. (family Ericaceae)

- Dogwood (genus Cornus)

Seed Sources

Seed pods of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) in fall by Mary Welz

If purchasing native plant seed, make sure to opt for reputable local suppliers, and always confirm that the species is correctly identified by its scientific name and that there is a high percentage of pure live seed. You could also responsibly collect your own seed from existing plantings or natural populations. Be sure to get advance permission to collect if you do not own the property, no matter whether it is public or private land. It is recommended to collect no more than 5% of seed (1 out of 20), to ensure that native plant populations can persist and thrive. Take care to identify and label the collected seed with the correct species name. Depending on the species, you may need to clean collected seed prior to sowing to remove any chaff. If you have seed to spare, you could participate in an expert-verified native seed swap in your area to trade for additional species to grow.

Seed Stratification & Sowing

Here in the Midwest and other temperate regions of the US, the ideal time to sow native plant seed is between late fall through mid-winter (December to February). The reason for this is that the seed of many types of native plants requires exposure to cold temperatures and/or moist conditions to stimulate germination (aka break dormancy). This requirement for seed stratification is a survival mechanism to ensure that seed does not germinate prematurely. Stratification occurs naturally when seed is sown outdoors and exposed to winter conditions. It is also possible to simulate this process by putting seed in a moist medium such as sand or soil and storing it in the refrigerator (or outside during winter) for a specific period of time. The length of time needed for stratification will vary by species.

Native plant seeds sown in reused plastic jugs in anticipation of the new year by Mary Welz

Small-scale

For smaller projects that involve growing potted native plants to install in a planned garden area or container garden, you can stratify seed by sowing outdoors in flats or other containers. A favorite technique of mine involves reusing clear plastic containers in which to sow seed, such as 1-gallon water jugs with a handle and narrow opening on top. In early spring, the containers act as a greenhouse to give young plants a head start as well as protect them from curious critters. In late spring or early summer, each seedling will then need to be transplanted into individual pots to become established before they are ready to plant outdoors.

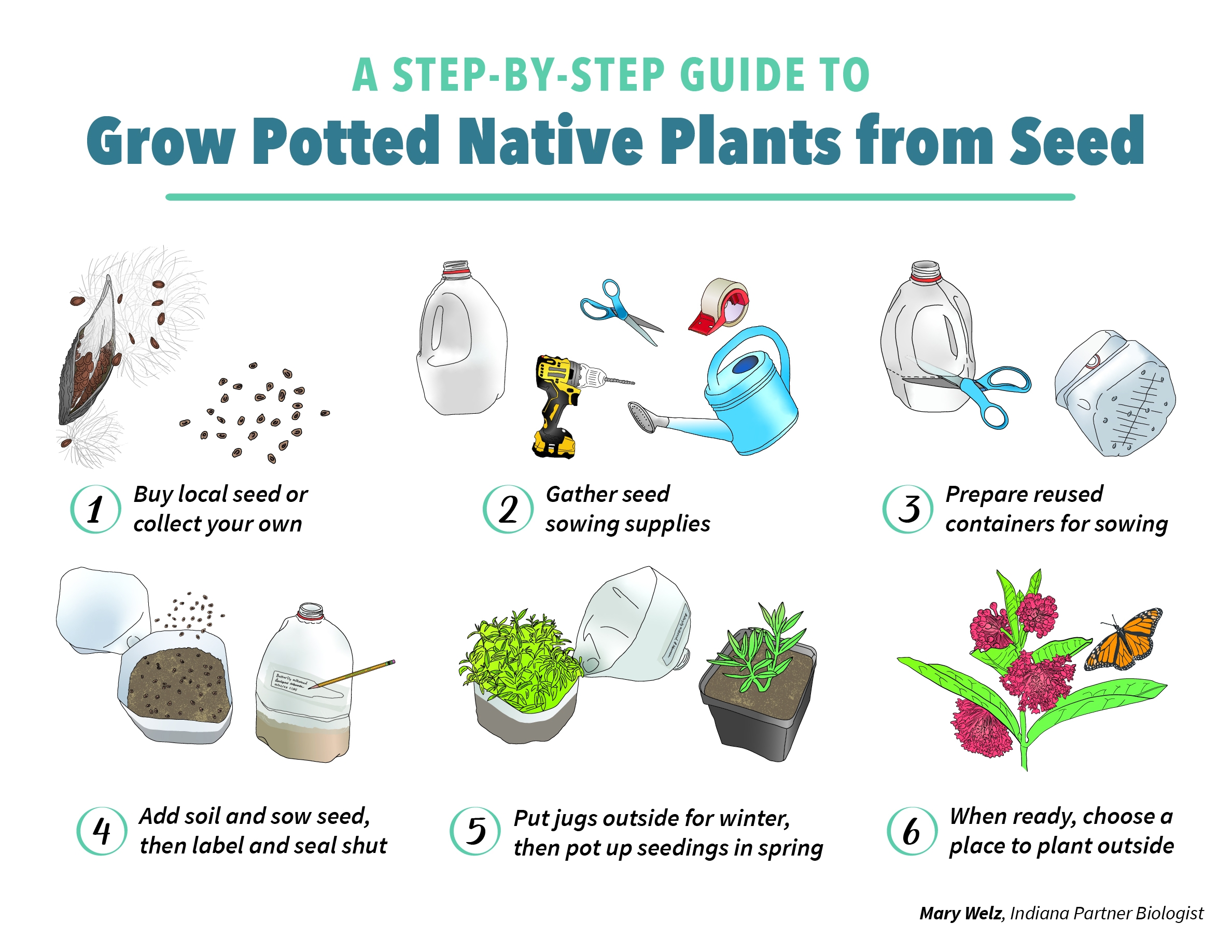

A Step-by-step Guide to Grow Potted Native Plants from Seed

- Get seed from a trusted source or responsibly collect your own. Clean seeds if necessary and store in a location that is cool, dark, and dry until you are ready to sow.

- To prepare jugs, draw a horizontal line about 4 inches from the bottom of the container, then cut along the line, leaving a section at the handle uncut to serve as a hinge. Drill or cut 10-15 holes on the bottom of the jug for drainage and remove the cap to allow rain and snow to enter.

- Add 2-3 inches of pre-moistened soil to the jug and gently tamp down to level and remove air pockets. Lightly sprinkle seed on top of soil, then cover larger seeds with a layer of soil or coarse sand, but only about as deep as the seed is thick. Surface sow very tiny seeds without covering. Only sow one species per container and be sure to label the container with the common & scientific name using weatherproof materials, then seal the jug shut with durable tape.

- Put jugs outside for winter in a place where they can get sun and precipitation but avoid direct southern exposure. Pick a spot with good drainage and secure them to make sure they don’t blow around. During winter, only water if there is a lack of rain or snow. Once the seedlings germinate in spring, water as needed but take care not to over-water! As spring progresses, open containers on warm days and close again at night until the chance of frost has passed.

- Once seedlings have at least four ‘true’ leaves, transplant them individually into small pots. Be gentle with the stems and roots during transplanting. Young plants will need continued care while growing in their individual pots. Depending on the species, they may be ready to plant outside within a month, but potentially longer.

- Choose a “forever home” location to plant them based on the growth requirements for each species. Plant native wildflowers in groupings of three or more of the same species to provide the most benefits to pollinators and people.

Diverse large-scale native pollinator planting by Amber Barnes

Large-scale

For larger direct to seed projects, in which you have a well-prepared seed bed accomplished through advance site preparation, frost sowing during the dormant season is an ideal method in which seed is broadcast onto snow covered and/or frozen ground. This practice provides the necessary conditions for seed to be stratified, and the natural freeze-thaw cycle also helps to situate the seed into the soil at the appropriate planting depth based on seed size. Sowing on top of snow-covered ground (ideally no deeper than 1 inch of snow) is also helpful to keep track of where and how much seed is spread. If there is no thaw in the immediate forecast after frost sowing takes place, be sure to add a thin layer of weed-free straw mulch to hold the seed in place. Mulch should also be used to protect the soil if there is potential for erosion such as on a slope.

The holiday season is the perfect time to constructively reflect on the past year and to set intentions for the year ahead. Growing your own native plants is both a symbolic and productive way to support pollinator habitat conservation at any scale. I encourage you to adopt this year-end ritual to grow habitat and hope for the new year!

Need help with your habitat installation?

Partner Biologist Technical Assistance

If you are a farmer or rancher interested in pollinator habitat, Pollinator Partnership has a team of Partner Biologists who are available to answer questions, share information about Farm Bill programs, and help access technical or financial assistance for pollinator habitat on agricultural lands.

To request resources or learn more about how you can support pollinators on your farm, visit the Meet Our Partner Biologists page for contact information and coverage areas. Or you can fill out the appropriate inquiry below:

Project Wingspan

If you would like to learn more about native plant identification and seed collection or volunteer to get involved, visit Pollinator Partnership’s Project Wingspan page or reach out to one of the Project Wingspan State Coordinators and Team Members.

Pollinator Steward Certification

To learn more about the Pollinator Partnership Pollinator Steward Certification training program visit the Pollinator Steward Certification page or contact psc@pollinator.org.

Bee Friendly Farming:

To learn more about Pollinator Partnership’s Bee Friendly Farming Certification Program visit the Bee Friendly Farming page or contact bff@pollinator.org.

Bee Friendly Gardening:

To learn more about the Pollinator Partnership Bee Friendly Gardening Certification Program visit the Bee Friendly Gardening page or contact bfg@pollinator.org.

References and additional resources:

- Few keystone plant genera support the majority of Lepidoptera species (2020 Narango, et. al): https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-19565-4

- Specialist Bees, Vermont Center for Ecostudies: https://val.vtecostudies.org/projects/vtbees/specialists/

- Host Plants for Pollen Specialist Bees of the Eastern United States (2020 Fowler): https://jarrodfowler.com/host_plants.html

- Pollinator Partnership Pollinator Habitat Installation Guide to Guides: https://www.pollinator.org/pollinator-habitat-guides