Island Buzz: How Hawaiian Pollinators Sustain Biodiversity by Phoebe Redfield, Pollinator Partnership

August 15th, 2024

ʻIʻiwi with an ʻŌhiʻa lehua bloom. Photo credit: Mark Kimora, National Park Service

Hawaii’s unique ecosystems thrive on the extraordinary adaptability and mutual relationships between its plants and animals. Pollinators play a crucial role in maintaining the island’s biodiversity, supporting intricate connections that have evolved over millennia. This blog explores the vital roles of native pollinators across the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaii’s isolation has given rise to numerous endemic species, such as Hawaiian honeycreepers (currently 17 species remain, with more than 50 species historically), and yellow-faced bees (Hylaeus spp.). These species have evolved unique adaptations that enable them to thrive in their specific habitats. The ʻIʻiwi (Drepanis coccinea), for example, is crucial for the pollination of native plants like the ʻŌhiʻa lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha), contributing significantly to the island’s ecological balance (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, n.d.; UH Honeybee Project, n.d.).

A Hawaiian yellow-faced bee. Photo Credit: Sheldon Plentovich and Jason Graham, Univeristy of Hawaiʻi

The Hawaiian yellow-faced bees, or nalo meli maoli, are essential for the pollination of many native plants. These bees are among the few native bees in Hawaiʻi and have developed specific relationships with native flora. Their decline due to habitat loss and the introduction of non-native species has serious implications for the plants that rely on them. Conservation efforts aimed at protecting these bees are crucial for preserving Hawaii’s unique biodiversity.

The relationships between plants and pollinators are vital for Hawaiian species. Coevolution has led to specialized adaptations that benefit both parties and make the decline in one species a great threat to the coevolved partner. The long, curved flowers of Hawaiian lobelioids, for example, are perfectly suited to the beaks of certain honeycreepers, demonstrating a coevolved partnership that ensures efficient pollination (UH Honeybee Project, n.d.).

The relationship between the ʻĀhinahina, or Hawaiian silversword (Agryoxiphium spp.), and its pollinators is another example of coevolution. The ʻĀhinahina, which grows in the high-altitude regions of Haleakalā on Maui, has evolved to rely on specific pollinators such as the Hawaiian yellow-faced bees. These bees are attracted to the ʻĀhinahina’s flowers, which provide a vital nectar resource in an otherwise sparse environment. The decline of these pollinators due to environmental changes poses a significant threat to the survival of the ʻĀhinahina.

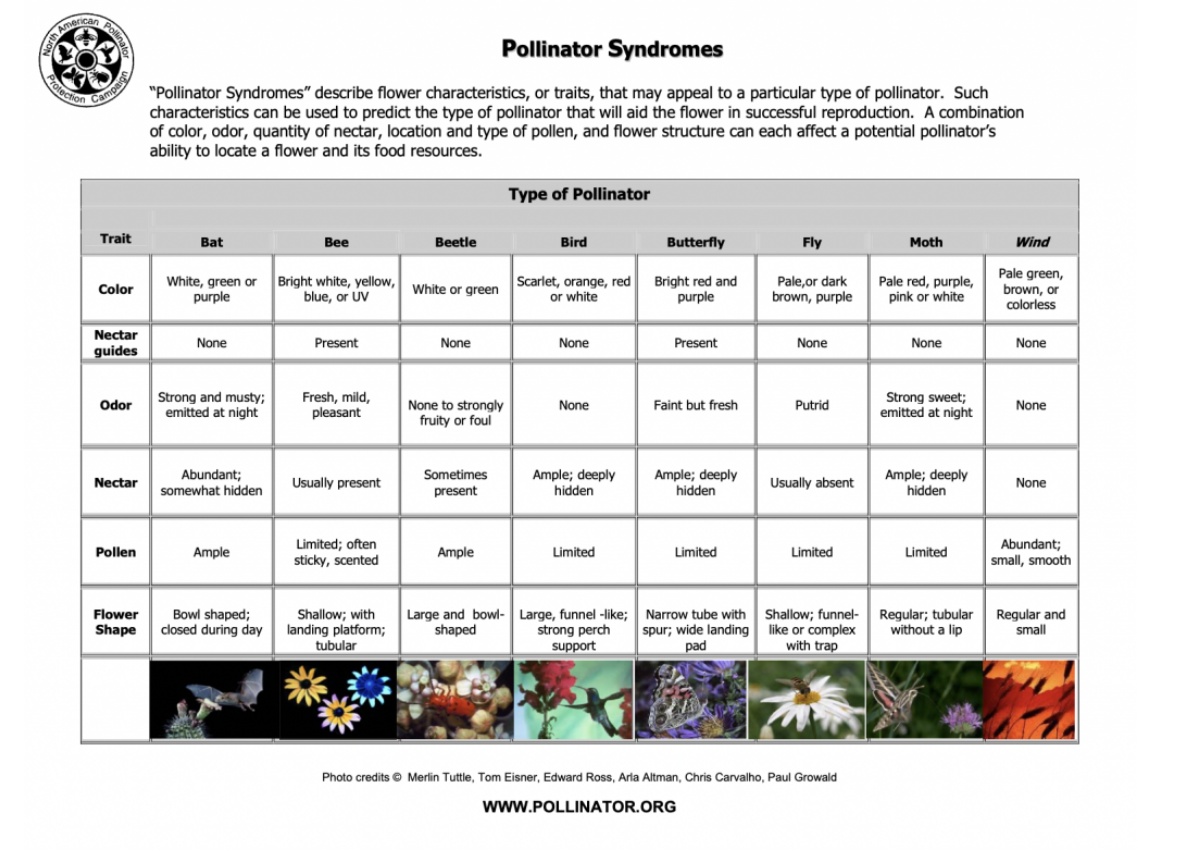

Pollinator syndromes describe the set of plant traits that have evolved over time to attract specific pollinators. These traits can include flower color, smell, shape, size, flowering time, “nectar guides” visual in the UV spectrum, and nectar composition. In Hawaiʻi, these syndromes are evident in various plant-pollinator interactions:

- Birds: Hawaiian honeycreepers are attracted to red, orange, and purple flowers with ample nectar and tubular shapes, aligning with their sensory preferences (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, n.d.; U.S. Forest Service, n.d.). The ʻIʻiwi’s curved bill is perfectly adapted to accessing nectar from the tubular flowers of the ʻōhiʻa lehua. This mutualistic relationship ensures that the plants are pollinated while providing a food source for the birds.

- Bees: Native bees prefer white, yellow, and blue flowers and utilize UV nectar guides to locate food. They are adept at handling challenging floral structures, such as those requiring buzz pollination (UH Honeybee Project, n.d.). For example, the Hawaiian yellow-faced bees are known to pollinate the flowers of the native naupaka (Scaevola spp.), which has specialized floral structures that the bees navigate effectively to gather nectar and pollen.

- Butterflies and Moths: Butterflies favor bright colors and flowers with broad landing pads, while moths, which are mostly nocturnal, prefer flowers that emit scents at night and have elongated corollas (UH Honeybee Project, n.d.). The Kamehameha butterfly (Vanessa tameamea), one of Hawaii’s few native butterfly species, plays a role in pollinating various native plants. Its preference for bright flowers and broad landing areas helps ensure the pollination of plants like the ʻōhiʻa lehua and mamaki (Pipturus albidus).

- Other Pollinators: Flies, beetles, and bats also contribute significantly to pollination. Hover flies (Syrphidae family), common in Hawaiian gardens, aid in pollination and pest control, while bats are drawn to dull-colored, musty-smelling flowers with abundant nectar (UH Honeybee Project, n.d.). The ʻōpeʻapeʻa, or Hawaiian hoary bat (Lasiurus cinereus semotus), although primarily an insectivore, also contributes to the pollination of native plants by transferring pollen as it feeds on nectar at night.

The mutualistic relationships between Hawaii’s native birds and plants are crucial for the island’s ecosystem. Birds like the ʻIʻiwi and ʻApapane (Himatione sanguinea) are essential for pollinating the ʻŌhiʻa lehua, a keystone tree species in Hawaii’s forests. These interactions ensure the reproductive success of these plants, supporting the broader ecosystem (U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, n.d.; UH Honeybee Project, n.d.).

The ‘Ākohekohe (Palmeria dolei). Photo credit: Jack Jeffrey, American Bird Conservancy

The native mamaki plant is another important species that relies on pollinators like the Kamehameha butterfly and various native bees. The mamaki is vital not only for its ecological role but also for its cultural significance, as its leaves are used to make traditional Hawaiian tea. The survival of this plant is closely tied to the health of its pollinators, highlighting the interconnectedness of Hawaii’s ecosystems.

Female Kamehameha butterfly on host plant mamaki. Photo credit: Nathan Yuen, University of Hawaiʻi

Recent research highlights the importance of protecting pollination and seed dispersal processes, which are among the most threatened by human activities such as habitat destruction and climate change. Conservation efforts in Hawaiʻi focus on preserving pollinator habitats, educating the public, and promoting sustainable practices to ensure the survival of these crucial species (Egerer, Fricke, & Rogers, 2018; Neuschulz et al., 2016; Pesendorfer, Sillett, Koenig, & Morrison, 2016; UH Honeybee Project, n.d.; U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, n.d.).

Programs like the UH Honeybee Project work to protect and restore native bee populations by creating habitats that support their nesting and foraging needs. Additionally, efforts to control invasive species and restore native plant communities are essential for providing the resources that native pollinators require. Public education campaigns also play a critical role in raising awareness about the importance of pollinators and encouraging community involvement in conservation efforts.

Hawaii’s unique ecosystems rely heavily on the intricate relationships between pollinators and plants. By understanding and protecting these relationships, we can help preserve Hawaii’s biodiversity for future generations. Supporting conservation efforts, appreciating the beauty of these interactions, and promoting sustainable practices are essential steps in sustaining Hawaii’s ecological balance.

References

Egerer, M. H., Fricke, E. C., & Rogers, H. S. (2018). Seed dispersal as an ecosystem service: Frugivore loss leads to decline of a socially valued plant, Capsicum frutescens. Ecological Applications, 28(3), 655-667. doi:10.1002/eap.1667

Neuschulz, E. L., Mueller, T., Bollmann, K., Gugerli, F., & Böhning-Gaese, K. (2016). Pollination and seed dispersal are the most threatened processes of plant regeneration. Scientific Reports, 6, 29839. doi:10.1038/srep29839

Pesendorfer, M. B., Sillett, T. S., Koenig, W. D., & Morrison, S. A. (2016). Scatter-hoarding corvids as seed dispersers for oaks and pines: A review of a widely distributed mutualism and its utility to habitat restoration. The Condor, 118(2), 215-237. doi:10.1650/condor-15-125.1

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. (n.d.). Bird pollinators. Retrieved from https://www.fws.gov/story/bird-pollinators

U.S. Forest Service. (n.d.). Bird pollination. Retrieved from https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/pollinators/animals/birds.shtml

UH Honeybee Project. (n.d.). Pollinators in Hawaiʻi. Retrieved from https://kohalacenter.org/docs/resources/hpsi/PollinatorsInHawaii.pdf

Learn More

About the UH HoneyBee Project: https://www.ctahr.hawaii.edu/wrightm/us.htm

About native Hawaiian birds, from the Maui Forest Bird Recovery Program: https://www.mauiforestbirds.org/birds/