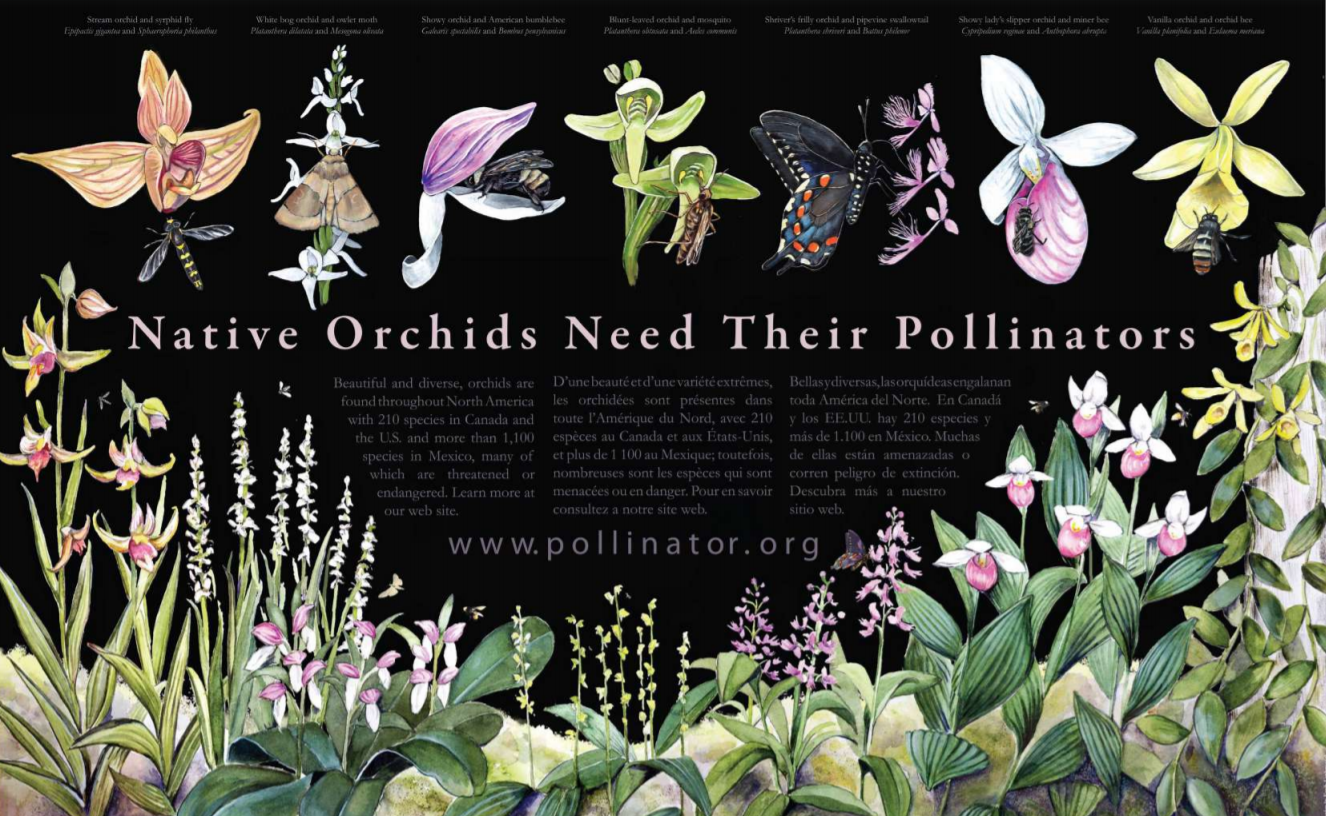

The "Native Orchids Need Their Pollinators" Poster

Beautiful and diverse, orchids are found throughout North America with 210 species in Canada and the US and more than 1,100 species in Mexico, many of which are threatened or endangered. Mature orchids produce highly modified flowers, and their colors, shapes, fragrances, nectar, and oils attract specific pollinators. Successful pollination renews the orchid’s life cycle for the next generation.

2014 Poster: Native Orchids Need Their Pollinators

DownloadPoster size is 24" H x 36" W

The Orchids

Orchid Overview

Orchid flowers are unique. Their male organs (one or two anthers) fuse to the back of the female organs (pistils). Both sets of organs work together to transfer pollen to a visitor and then collect it again when the insect enters a second flower encouraging cross-pollination. With the exception of milkweeds (Asclepias) and their allies, orchids are the only plants on this planet that release their pollen as discrete balls (pollinia) and each ball may contain thousands to millions of compacted grains. As the pollen-accepting tip (stigma) of an orchid has space for only a few pollinia this means that, quite often, all the seeds in the same orchid pod have the same father flower.

The successful transfer of pollinia then makes all the difference between orchid motherhood and extinction. Lots of animals visit orchid flowers but each orchid species often has “preferred” pollinators. An orchid flower that is pollinated by queen bumblebees has a floral architecture that makes it improbable that visiting moths or butterflies will pollinate it no matter how hungry they are. Around the world different orchid species may be pollinated by different members of seven different families of bees, several families of wasps, nectar-drinking flies, butterflies, sphinx and settling moths, hummingbirds and African sunbirds. No bat-pollinated orchids are known to date but on the island of Reunion, in the Indian Ocean, at least one species (probably more) night-blooming orchids is pollinated by a raspy cricket.

In North America, we see only a few orchids pollinated by hummingbirds in Mexico. All remaining species are pollinated by insects, but that can include some rather unusual creatures including clear wing hawkmoths and mosquitos. Once we enter the warmth of Mexican forests we find hundreds of species of specialized bees in which the males visit orchid flowers to collect perfumes. They use these scents to mark their territories and, more often, they make colognes that will attract other males. These males hold massed mating displays (leks) attracting females. These tropical orchid bees receive their own tribe, the Euglossini. Recently one of these “orchid bees” established itself in Florida.

In the 19th century wealthy people started collecting tropical orchids for their new greenhouses and they dissected the flowers. Amateur botanists were perplexed. Why did they have such unusual shapes and why did male and female organs fuse together to form a reproductive structure they called the column? Charles Darwin observed wild orchids around his home in Kent, England for 20 years, but also received and studied plants from the tropical Americas and Africa. He published his findings in 1862 and revised them in a second volume in 1877. Read it today and you can see how he came to the conclusion that the unusual forms of the flowers were adaptations that helped transfer pollinia between flowers when insects came for nectar or other foods. He noted, for example, that different orchids deposited their pollinia on different part of different insect bodies. Butterflies and moths still tend to carry the pollinia at the bases of their tongues while bees and wasps are more likely to carry them on their heads or backs (often between their wings). At times, Darwin pretended he was an insect inserting pencil tips, pins and straws into the flowers and then removing them to see if he had withdrawn the pollinia. To help prove his points, Darwin employed a scientific illustrator (G.B. Sowerby) to draw the interiors of dissected flowers, changes in the pollinia as they dried and a moth head wearing pollinia at the base of its tongue.

What Darwin didn’t know is that many orchids trick insects into pollinating the flowers. The color and odor of some orchids looks enticing but there’s absolutely nothing to eat inside and no perfumes worth collecting. For example, all of our lady’s slipper orchids (Cypripedium) do this whether they are pollinated by big, queen bumblebees (C. acaule),or tiny sweat and halictid bees (C. arietnum).

Cypripedium arietinum

C. parviflorum

C. montanum

The lip petal (labellum) of grass pinks (Calopogon) wear skinny, yellow lollipops that bumblebees mistake for pollen-filled anthers. Pictured on the right.

All orchid species that are cross-pollinated must have an animal pollinator (no wind or water-pollinated orchids) but no pollinator is entirely dependent on orchid nectars or perfumes to survive. Even those male orchid bees that must collect scents to reproduce have the option of shopping for chemicals from the resins and leaf and tree bark or from completely unrelated flowers like tree tomatoes (Cyphomandra) and flamingo tongues (Anthurium). Orchids must compete for pollinators, especially the ones they trick.

This competitive mode has been unusually successful as the family of orchids is one of the largest in the world. There may be over 20,000 species on this planet as new ones are described monthly. Some botanists speculate that one out of every 10 plant species on the planet is an orchid but the vast majority is found around the equator. Distribution of orchid species in North America seems unfair without a big tropical zone. Mexico has over 700 species but the continental United States has only 100 and Canada just 30. The good news is that some orchids really like cold bogs and tundras, so you can find over 25 species in the brief summer of the Alaskan panhandle onto the Kodiak and Aleutian islands.

Orchids need their pollinators even when their pollinators don’t always need them. As we can see, though, many North American orchids and some pollinators have grown increasingly rare. Extensive colonies of riverside and valley orchids seen by Henry David Thoreau and John Muir in the 19th century are harder and harder to find, just like the bumblebee, Bombus bimaculatus. To help protect these species, please don’t pick the plants or try to transplant them (they won’t survive). Refrain from buying tropical species from Mexico or Florida unless you know their seeds were grown in a greenhouse or by cloning potted plants (man-made hybrids are fine). If you find them on a hike why not share them in photos? You can help scientists by photographing pollinators at the flowers and reporting the populations you find to botanic gardens, the US Forest Service and to plant biology departments at local universities.

Orchid Identification

1. Stream orchid - Epipactis gigantea

Geographic Distribution: Northwest from the borders of British Columbia south through Mexico and eastwards along the Blue and Rocky Mountains entering Oklahoma and Texas.

Pollinators: Hoverflies (Syprhidae) searching for nectar

Habitat: At elevations from 40 to 2,500 m above sea level. Often follows creeks and stream banks and can tolerate both hot and brine springs.

Size: One of the tallest, terrestrial orchids in Canada and America from 30 – 100 cm tall in bloom

Bloom Period: From March (southwards) through August (north)

Color: A yellowish and pink background with striking red-purple veins on petals and sepals

Other: It’s the biggest species in the genus Epipactis (70 species in Europe and Asia) and the ONLY member of the genus truly native to North America. The name, giant helleborine refers to the fact that in Europe, herbalists often confused their much smaller, native Epipactis species with the medical hellbores (Helleborus) in the buttercup family (Ranunculaceae).

Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Epipactis

While there are more than two dozen helleborine orchid species in Europe, Asia and Africa our stream orchid, E. gigantea is the only Epipactisspecies native to North America. Yes, we do have a few populations of Epipactis helleborine in northeastern America and Canada but it seems to have been introduced accidentally from Europe. We also know our E. gigantea as the chatterbox and the giant helleborine. Its hinged, striped, lip petal may bounce up and down on breezy days making the tip of the petal resemble a wagging tongue. Compared to the helleborines of the Old World it really is a giant producing a stem that can grow 3 ft high. The plants appear to do well among sand, gravel and stones along creeks and riversides. Some populations actually seem happy and robust around hot or even salt springs.

2. White bog orchid - Platanthera dilatata

Geographic Distribution: Absent from Mexico, it is found from the Arctic Circle into the Alaskan panhandle then eastwards through most of Canada heading southwards to Pennsylvania, around the Great Lakes then into the wetter northwestern states including northern California.

Pollinators: May be visited day or night as skippers fly by day but so do some nectar-drinking owlet moths (Noctuidae). These moths do not hover while they feed from orchids, unlike the better known sphinx moths (Sphingidae). They are settling moths and must land on the flower like a bee or hoverfly.

Habitat: Wet tundra, meadows, moist forest edges and natural seeps. Sometimes in cold, swampy fens flowing above limestone deposits.

Size: Flowering stems 11 – 130 cm

Bloom Period: May through August, depending on latitude and variety

Color: White often with greenish yellow throats.

Other: People really like the spicy odor of the flowers although spicy scents are more often associated with tropical orchids with much larger flowers. Botanists break this species into three varieties (albiflora, dilata and leucostachys) based on geography and the length and shape of the nectar-secreting spur. Is the spur longer or shorter than the length of the lip petal? The different lengths and shapes of the nectar-secreting spur strongly suggests that different moths pollinate this orchid over its broad range.

Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Platanthera dilatata

Also known as fragrant orchid, scent bottle, white northern orchid, white rein orchid and bog candles. Like most orchids there is only one pollen box (anther) in the center of the flower but it is so broad and flat scientists named the entire genus Plat = broad and flat, anther = anther. A single flowering stem of bog orchid may bear a hundred flowers with most of them open at the same time. Some people say they smell like cloves. Native people living in Alaska and Canada dug them up, boiled the starchy underground storage organs (tuberoids) and ate them like potatoes.

3. Showy orchid - Galearis spectabilis

- Geographic Distribution: Eastern Canada (southern parts of Quebec, Ontario and Newfoundland) south through America’s eastern states but it never reaches Florida and is found as far west as Kansas and Oklahoma.

- Pollinators: Queens of various bumblebees visit the flowers for nectar in mid-spring in America but in Canada, common visitors include native orchard bees or leafcutters (Osmia). Some people have seen butterflies visiting these flowers but their effectiveness as pollinators remains unstudied.

- Habitat: Usually refuses to grow in full sun. They prefer ravines in open woodlands of deciduous trees especially mixtures of beech (Fagus), maples (Acer) and tulip trees (Liriodendron) where there is dense humus. Where this species does well you may also find such native orchids as the yellow (Cypripedium parviflorum) and pink (C. acaule) lady’s slippera, as well as the crane fly orchid (Tipularia discolor) and the Adam and Eve orchid (Aplectrum hyemale).

- Size: Short, compact and the flowering stem is rarely more than 20 cm high.

- Bloom Period: As early as April in the southern parts of America but the plants wait until June to July in Canada.

- Color: Easily recognized by its red-violet to purple helmut. The lip is white but may be “dusted with pink.” Rare, all white forms are known (willeyi form). Some botanists call the all pink-flowered form, gorinierii.

- Other: May “lose” bumblebee pollinators to yellow flags (Iris pseudacorus)if they bloom together. A single pod of the showy orchids can contain over 7,000 seeds. The dust-like seeds of most orchids are supposed to have a short life span but tests on G. spectabilis show they stay dormant and healthy in soil for up to six months. This orchid seems to be extremely sensitive to soil chemistry, shade and man-made disturbance.

- Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Galearis

There is only one species of Galearis orchid in North America and our wildflower is found from southeastern Canada, through New England extending through the American Midwest and just south of the Mason-Dixon line. Canadian and New England plants may bloom as late as July while those in America’s southlands can be found as early as mid-April. A cousin (Galearis diantha) is found in China. Flowers are rarely pure white and usually wear a pink-purple to rich reddish purple “helmut” (galea = helmut). While some plants bloom in old fields most appear to grow best in moist, wooded ravines with trilliums and jack-in-the-pulpit. As this species becomes increasingly harder to find local naturalists may be able to show you some plants if you refer to them under their other common names including gay orchis, purple orchis or purple-hooded orchis or even two-leaved orchis. The lip petal has a hole at its base leading to a hollow spur that containing a droplet of nectar. The queens of at least five bumblebee species drink the nectar of this orchid and pollinate the flowers. In Canada, though, the most important pollinator may be a smaller orchard bee (Osmia proxima).

4. Blunt-leaved orchid - Platanthera obtusata

- Geographic Distribution: Follows the Arctic Circle from Alaska through Canada. It grows as far south as New York in the American east and Oregon in the west. Some botanists insist the same species is also found in Scandinavia, Siberia and Korea calling it P. obtusata subspecies oligantha.

- Pollinators: Female mosquitos (Aedes), a snout moth (pyralid) and an inchworm moth (geometrid) pollinated these flowers. The blunt-leaved orchid rewards them with nectar nectar at the tip of its tiny, hollow spur even though it’s only 3 - 8 mm in length.

- Habitat: Prefers a wide range of wet cold sites including spruce forests, sphagnum bogs, tundra and along roadside ditches.

- Size: Usually less than 10 cm tall, it may be as high as 35 cm

- Bloom Period: Usually a summer flowerer from June to August.

- Color: Green to greenish yellow.

- Other: Reports of mosquito pollination in this orchid date back to 1913. It was hard for botanists to believe but then more observations arrived from other field scientists in the 1950s and 1960s. There was only one report from Alaska in 1955 of male mosquitos carrying the pollinia of this orchid. All other reports show the females do it. At least four different species of Aedes have been found carrying the pollinia but A. communis receives the most. Moths known to pollinate this orchid include Eudonia lugubralis (Pyralidae) and Xanthorhoe munitata (Geometridae).

- Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Platanthera obtusata

Found in bloom from June through August in wet forests of pines and other conifers. It also likes cold, sphagnum bogs and true tundra. While we think of this wildflower as a summer plant of Alaska, Canada and New England the exact same species is also found in Siberia, northern China and Asian countries that were once part of the old Soviet Union. Their skinny stalks rarely bear more than 15 flowers. Female mosquitos aren’t the only pollinators of these little, green-flowered orchids. They are also pollinated in part by small, nectar-drinking, snout mouths (pyralids).

5. Shriver's frilly orchid - Platanthera shriveri

- Geographic Distribution: A wildflower of the Appalachias it was first discovered in West Virginia in 1992 and represents a “new” orchid species for America described in 2008. Records in plant museums (herbaria) suggest it’s found from southwestern Pennsylvania to western North Carolina. It may grow with purple-flowered P. grandiflora and with a natural hybrid between P. grandiflora the white-flowered P. lacera.

- Pollinators: Almost all of the larger, colorful (purple, pink, orange, yellow) Platanthera orchids in North America are pollinated by a combination of large butterflies, day-flying moths and skippers. Photographic evidence of pipevine swallowtails pollinating Shriver’s frilly orchid are quite recent. As in most butterfly-pollinated orchids the sticky disc (viscidium) of the pollinia packets becomes attached to the base of the butterfly’s tongue or its large compound eyes. There’s every reason to suspect that this orchid is pollinated by other large butterfly species.

- Habitat: Found in partial to full shade in mixed deciduous and pine forests along springs and streams or on roadside banks colonized by mosses, ferns and sedges. Most common at elevations between 850 – 1450 m (2350 - 400 ft).

- Size: 35 – 110 cm

- Bloom Period: Mid to late July

- Color: Light to pale purple (mauve)

- Other: The current theory is that this orchid is the ancient results of past hybridization between P. grandiflora x P. lacera. Butterflies did the original job and the hybrid has become stabilized by a process of backcrossing known as introgressions.

- Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Platanthera shriveri

Botanists recognize more than 30 species of Platanthera orchids in the United States alone but the large-flowered species with the sweetest scents and fringed petals prefer to grow in seeps, swamps and sphagnum bogs and are the favorites of hikers (especially when the bloom en masse). Botanists often fail to agree about how to identify these orchids to species especially plants bearing pink to purple blooms as they have a history of hybridizing with each other and to Platanthera species with white flowers. Platanthera shriveri is a controversial “new species” of the Appalachian mountain range, first described in 2008. While people have been studying it since the 1990’s it was not recognized as a real species in Volume 26 of Flora of North America (2002). Some treat Shriver’s frilly as a late flowering form of Platanthera grandiflora. Others suggest it is one of several populations of hybrids between one of the purple flowered Platanthera species and the whitish-green P. lacera. These naturalists contend that Shriver’s frilly orchid evolved from hybrid stock by a process of backcrossing between hybrids and parent species (properly known as introgression). Whatever the case, Shriver’s frilly remains popular with large butterflies as a nectar resource. Some scientists suspect that the fringes and frills on the species of Platanthera with large, colorful flowers represent hidden perfume glands (osmorphores).

6. Showy lady's slipper orchid - Cypripedium reginae

- Geographic Distribution: From Labrador (Newfoundland) as far west as the southern borders of Saskatchewan then south throughout New England, the Great Lake states on to North Dakota. Found as far southwest as Missouri.

- Pollinators: Visited by a wide range of tiny beetles, hover flies and even flower beetles but medium-sized bees (10 – 14 mms in length) in the families Apidae and Megachilidae appear to be the only insects that are effective removing the smeared, sticky pollinia as they escape the flower.

- Habitat: Seems to like coarse, calcium rich soils in gaps in both soft and hardwood forests but also exposed in fens and on the edges of cliff seeps.

- Size: The tallest slipper orchid in Canada and America. It produces a stem from 21 – 90 cm high and is the only slipper orchid in North America in which foliage leaves grow up and down the stem (cauliflorous).

- Bloom Period: June to July (northern distribution) Mid-May (southern distribution). Flowering stems rarely produce more than one terminal flower.

- Color: Inflated sac or lip petals all reddish-pink or with a pink blush. Look for the trail of pink-purple spots on the inside of the sac. The lateral petals and dorsal sepal s are usually a waxy white. Pure white flowers have been found.

- Other: Orchid breeders in China and Europe have crossed our North American showy slipper with its Asian “sister,” C. flava. These expensive plants often go on sale in fancy bulb catalogs. All slipper orchids are traps. When the insect enters or falls into the sac or bucket the only escape is to crawl up the sac, under the sexual organs and escape through one or two holes. That forces the bee to rub against the open anthers smearing it with pollinia. Most large bees refuse to fall for this trick twice so, even in a good year, less than 25% of the flowers of the showy slipper set fruit.

- Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Cypripedium reginae

The Swedish botanist, Linnaeus, must have loved the colorful, pouched labellum petal of slipper orchids as he named the genus, Cypripedium, in honor of the beautiful, slipper wearing feet of Aphrodite (the patron goddess of Cyprus). Therefore, it shouldn’t surprise us that C. reginae is also the queen lady’s slipper (regina = queen). There are at least 13 slipper orchid species found from Canada to Mexico. Our showy lady’s slipper has the third largest petal sac (labellum) in North America after the more common pink slipper (C. acaule) and the even rarer Mexican, pelican flower (C. irapeanum). Our showy slipper may be found from eastern Canada through New England and much of the eastern seaboard westward through our Great Lakes and south into Missouri. It is the state flower of Minnesota and the provincial flower of Prince Edward Island (Canada). It prefers to grow in bogs or along trickling creeks and mossy beds that remain moist at least during mid-spring. Unfortunately it has also grown increasingly rare due to habitat destruction and vandalism. The beautiful sac is devoid of nectar and, like all slipper orchids studied since the early 20th century, it lures insects into its “pouch” with vivid colors and false promises. The Showy slipper specializes in deceiving medium-sized bees like the Anthophora abrupta and various members of the leaf cutter bee family (Megachilidae) while the pink lady’s slipper tricks queen bumblebees. Recent gene studies confirmed that the showy slipper has a “sister species” in China but is has yellow flowers (C. flava). While our showy lady’s slipper does have a fragrance human beings find it faint or odorless as our noses are not able to pick up low concentrations of methyl salicylate (wintergreen oil).

7. Vanilla orchid - Vanilla planifolia

- Geographic Distribution: From eastern Mexico to Guatemala then in watersheds on the Caribbean sides of Belize and Honduras. It has escaped into southern Florida and “weedy vines” have been reported from Long Pine Key, the Everglades and in the Miami-Dade County area. There are about 107 Vanilla species found on continents around the equator (excluding Australia) but only V. planifolia, and its Mexican sister, V. pompona, are species of commerce. The gourmet, V. tahitenensis turns out to be a mutant of V. planifolia.

- Pollinators: So far, three species of Eulaema bees are associated with the pollination of wild plants. Without help only 6% of vanilla flowers form fruits.

- Habitat: A vine of tropical evergreen forests, they start life on the ground and then scramble up trees or rock formations. Appears to prefer soils deposited over sedimentary limestone. Wild populations of this species in Mexico are now regarded as endangered due to habitat destruction.

- Size: Difficult to measure in the wild but domesticated vines may extend from 20 – 100 ft if they like their conditions.

- Bloom Period: A single flowering stem can produce as many as 15 buds but most vines stagger blooming and rarely open more than one or two flowers on the same day.

- Color: Light yellowish to creamy white or ivory. The short-lived flower may become increasingly yellow as it ages over the course of the day.

- Other: The most important orchid of commerce and world cuisine but not for its flowers. The green pods are picked and allowed to ferment in special curing houses. The acting of curing each pod requires four stages (killing with dry heat, sweating in a hot humid environment, drying in the shade and conditioning in boxes for 3 – 6 months. No wonder they are expensive. They turn black and release the molecule vanillin and other essences. Vanilla extract is made by soaking the conditioned pods in a solution of alcohol and water, brandy will do, for three weeks or more. It’s one of the few orchids to produce crusty instead of dusty seeds so the French cooks often prefer to split the pods, dig out the seeds and add them directly to various sauces or desserts. When grown in greenhouses they can turn into rampaging vines covering entire walls and ceilings. While the conquering Spaniards started vanilla plantations as early as 1760 the hand-pollination of commercial vines didn’t begin in Mexico until 1840. The new technique was adopted rapidly by the Totonac Indians much increasing the world supply.

- Go Orchids: North American Orchid Conservation Center: Vanilla

Yes, this is the wild version of the domesticated vine whose fermented fruit gives us the flavor of vanilla. The Aztecs appeared the first to combine their chocolate with the essence of fermented vanilla pods and other herbs to make a beloved beverage that the Emperor Montezuma supposedly served to the conquistador Cortez. Mexico continues to export vanilla pods commercially but, the vines were exported to other countries over the centuries, (including Madagascar) and trained workers always hand pollinate the flower with sticks to maintain the highest yield of pods. This must be done quickly as, unlike so many other wild orchids, the blossoms of vanilla rarely live for a full 24 hours (only 8 hours for some flowers). Old stories insisting that this flower is pollinated exclusively by the Mayan honeybee (Melipona beechei) are incorrect. Based on a study published in the journal, Lindleyana in 2006, V. planifolia depends on several species of medium-sized to large, orchid bees in the genus Eulaema. To clarify, Eulaema cingulata, E. polychroma and E. meriana, as well as Euglossa viridissima and Melipona beecheii (Mexico) are commonly found in Central America and northern South America to pollinate the vanilla orchid.

The Pollinators

Pollinator Overview

Pollination occurs when pollen is moved within flowers or carried from flower to flower by pollinating. Almost 90% of all flowering plants rely on animal pollinators for fertilization, and about 200,000 species of animals act as pollinators. Of those, 1,000 are hummingbirds, bats, and small mammals such as mice. The rest are insects like beetles, bees, ants, wasps, butterflies and moths. Plants can also be pollinated by wind and water. The transfer of pollen in and between flowers of the same species leads to fertilization, and successful seed and fruit production for plants. Pollination ensures that a plant will produce full-bodied fruit and a full set of viable seeds.

Worldwide, approximately 1,000 plants grown for food, beverages, fibers, spices, and medicines need to be pollinated by animals in order to produce the goods on which we depend. In the United States, pollination by honeybees and other insects produces $40 billion worth of products annually

Learn more about the pollinator lifecycle here and how you can help protect them here!

Pollinator Identification

1. Syrphid fly - Sphaerophoria philanthus

- Geographic Distribution: From Canada, through California, down to Mexico, and Florida.

- Habitat: This is a widespread species of heathland, bogs, mire, moorland, heathy woodland rides and coastal dunes - especially in damper areas where Purple Moor-grass, cotton-grasses and rushes are present. Wheat crop and grass fields, forest floor.

- Size: 7.6 - 9.6 mm

- Identification: One pair of iridescent wings and big eyes. Black and yellow stripes with a long thin abdomen that curves slightly under at the end. The abdomen is about 3 times longer than the stout, bulbous thorax. Six yellow legs with the hind pair much longer than the fore-pairs. Short tongue.

- Other Plants Commonly Visited: Flowers like Tormentil and Heath Bedstraw.

Flies are among the most frequent visitors to flowers and important pollinators of a wide range of plants. Syrphid flies are often referred to as flower flies. This group exhibits a characteristic flight pattern where they hover and can abruptly change their position. They are called hover flies in Great Britain. Syrphid flies can be easily mistaken for bees and wasps. However, flies have only one pair of wings while bees and wasps have two. Their large eyes, short antenna also give them away. They also have nowhere to carry pollen. Of the nearly 900 species of flower flies (family Syrphidae) in North America, most have yellow-and-black stripes.

2. Owlet moth - Mesogona olivata

- Geographic Distribution: Occurs from British Columbia to California, Colorado and Texas. Most likely can be found in Northern Mexico.

- Larvae Characteristics: Larval foodplants include a diverse assortment of woody plants such as poplar, oak, hazel, Amelanchier Medic., alder, antelope brush, Symphoricarpos Duhamel and Berberis L.

- Habitat: Wet forest to semi-arid steppe.

- Size: Forewing length 15 - 20 mm and 2xs as long as wide.

- Identification: Most specimens are brownish but reddish morphs can be common. Forewing reddish brown. Hindwing gray, vesica of aedoeagus with two distal bands of short thin cornuti, appendix bursae overlapping corpus bursae ventrally, long “tarsal claws” or first legs.

- Other: Individuals from semi-desert locales tend to be pale while those from more mesic forest are darker. M. olviata is sympatric with both other Mesogona species.

Genotype of Mesogona. Considered to be the “Old World” species of Pseudoglaea (genus). There are five species in this genus, two in Eurasia and three in North America. Until recently only one North American species, olivata Harvey has been described. M. olviata was more recently discovered in observations in Oregon and Washington. Adult moths are most active and lay their eggs in the fall when foliage is changing color. The larvae hatch in the spring feeding on a variety of woody plants. Moth coloring often resembles the bark of the foodplant it prefers. This is most likely a protective adaptation.

3. American bumblebee - Bombus pensylvanicus

- Geographic Distribution: Eastern North America, from Quebec to Florida west to Colorado, Texas.

- Nest Characteristics: Nests on ground surface.

- Habitat: Large fields

- Size: Large, Queen 21 - 25 mm, Worker 14 - 18 mm, Male 16 - 22 mm

- Identification: Female’s top of the head black, thorax with yellow band(s), T1 often yellow especially in the middle, T2-3 yellow, tail black, face long. Midleg basitarsus with the distal posterior corner sharply narrowly produced and spinose, hind basitarsus with the proximal posterior process long and pointed (longer than broad). Cheek slightly longer than broad, clypeus with large punctures except on the mid line. Hair on the top of the head always black, T1 with yellow hairs more frequent medially. Hair short and even. Males have a yellow abdomen with a black head and black striping in the lower thorax.

- Other Plants Commonly Visited: Vetches, clovers, goldenrods, St. John’s wort, boneset

- Other: Uncommon, possibly in decline. Parasitized by B. variabilis.

There was a time you could find this bumblebee across most of North America from Quebec to Florida, westward to South Dakota then south into the central Mountains of Mexico. Within the past decade, though, its numbers have collapsed and it is strongly suspected it was infected with a virus when European bumblebees were imported into North America to pollinate greenhouse tomatoes. In spring the overwintering queens of our American bumblebee pollinate many spring wildflowers. It’s fun to watch these plump ladies hang upside down while they forage on the nodding flowers of trout lilies (Erythronium) or columbines (Aquilegia). Of course, they are collecting nectar and pollen to feed to their first brood of workers. Once the workers mature the queen stays home and her daughters pollinate the wildflowers and bushes of summer and autumn. Like most bumblebees in Canada and America the colony is annual. The queen dies in the autumn cold weeks after she produced new queens in late summer or early fall.

4. Mosquito - Aedes communis

- Geographic Distribution: True snowpool species that is most common in the northern U.S. and Canada to Alaska. Most commonly found in New Jersey.

- Larvae Characteristics: Larvae are present in late March and most often begin pupating during the 3rd week of April. Larvae are most common in deep snowpools filled with dark colored water in forested areas above elevations of 1500 ft. Usually the only large species mosquito present in a given pool.

- Habitat: Heavily forested areas at high elevations.

- Size: Large

- Identification: Upper and lower head hairs are usually single, occasionally double. Antenna length is shorter than head and the tuft is inserted before the middle of the shaft. Long pointed gills frequently have a rusty color. Patched comb scales. Pecten is evenly spaced. In the anal segment the saddle is incomplete and with 2 - 4 precratal tufts.

- Other: Ades communis is a major pest in the Adirondacks in New York State and the Pocono Mountain range in Pennsylvania. It is one of the earliest mosquitoes to appear in the northeast monocyclic species.Sacks of pollen or pollinium can be seen carried by mosquitos after visiting pollen rich flowers. See yellow pollinium in the photo above.

We all know that female mosquitos bite and drink blood to provision the next generation of eggs but where do they get the energy to pester us? Some consume the sugars in flower nectar to fuel their attacks on us. Here in North America, at least 15 species in the genus Aedes are known to drink the nectar of small-flowered, greenish orchids placed in the genus Platanthera. A paper suggesting that they also pollinated the orchid appeared in 1913. There’s no doubt now that, this insect has mouthparts long enough to reach the nectar in the orchid’s little spur. As she prepares to leave her the flower her head touches the sexual organs in the flower’s column and two golden “eggs” of pollen (pollinia) are deposited on her face because the eggs come complete with their own little stalks and sticky suction cups. Cross-pollination occurs when she visits a second flower on a second plant. Of the 15 species, Aedes communis is the best studied as it is so common on summer tundras and bogs where these little orchids may thrive. The great American authority on native orchids, Carlyle Luer, described how they hummed in swarms around the blunt leaf orchid carrying so many bright yellow balls of pollen the insects looked like they were wearing their own head lamps. Therefore, while this mosquito may be a bit…annoying...it should not be confused with its bad cousin, A. egypti, known to transmit yellow and dengue fevers.

5. Pipevine swallowtail - Battus philenor

- Geographic Distribution: Southern half of the U.S. to southern Mexico.

- Larvae/Egg/Chrysalis Characteristics: The eggs are red-orange and circular. The caterpillars are black with red projections and spots running down their backs. These colors can be affected by temperature with warmer climates resulting in shades from black to red. The chrysalis’s posterior end is segmented and has an inward curve. The ventral thorax is raised and the head has a pair of horns at the anterior dorsal portion.

- Habitat: Mostly warm climates in open woodlands, meadows

- Size: Wing span 2 ¾ - 5 in.

- Identification: Fore-wing of adults is black above and gray below. The dorsal hind-wing is where sexual dimorphism is obvious. Males have smaller cream or pale spots than females, and the spots run along the fringe of the wings. Males are brighter metallic blue in the dorsal hind wing region. Bottom half of the ventral hind wing of both sexes is metallic blue. A single row of seven orange spots and small pale, cream dots are found at the edge of the wing embedded in the blue section.

- Other Plants Commonly Visited: Thisles, bergamot, lilac, viper’s bugloss, common azaleas, phloc, teasel, dame’s rocket, lantana, petunias, verbenas, lupines, yellow star thistle, California buckeye, yerba santa, broiaceas and hilias.

- Other: Females lay clusters of eggs on or under pipevine leaves, usually exposed to the sun. Pipevine leaves are actually toxic to many other animals, this helps protect the caterpillars.

It’s easy to confuse this striking butterfly with the black swallowtail (Papilo polyxen)as both species have dark forewings and you can find some black swallowtails that also wear iridescent blue on their hind wings. The black swallowtail comes into our gardens to lay eggs on carrots, dill, parsley and other members of the celery family. In contrast, the caterpillars of our pipevines eat only the leaves of birthworts and dutchman’s pipes (Aristolochia). If you want to lure these butterflies into your garden you should provide them with birthwort vines available from native plant nurseries and seed companies. These woody vines are rather primitive and related to magnolias but native, American birthworts are pretty easy to grow if you have some dappled shade and add humus to your soil.

6. Miner bee - Anthophora abrupta

- Geographic Distribution: From Texas to the east coast of the U.S., from Florida to Canada.

- Nest Characteristics: Solitary, ground nesting bee. Females dig a tunnel, often in clay. Nests are clustered together but females only provide for their own nest and future offspring.

- Habitat: Well-drained soils to nest in such as banks, hills and road cut-outs

- Size: The adult female A. abrupta are 14.5 – 17 mm long and the adult male A. abrupta are 12 – 17 mm long.

- Identification: The head, legs and abdomen are lightly covered in brown-black hairs while the thorax is covered in dense, pale yellow-orange hairs. The wings are nearly transparent to slightly cloudy with brown-black veins. The males have a distinctive set of hairs on the margin of their yellow clypeus, like a mustache. The males carry pheromones attractive to females in their mustaches. The female’s cheeks are approximately the same width as their eyes and they have a strongly protuberant clypeus (the area on the center of the face between the eyes and mouth).

- Other Plants Commonly Visited: A. abrupta has been recorded to visit many flowers and is considered a forage-plant generalist that will nest in the same location for many years.

- Other: Non-aggressive bees and do not typically sting.

This chunky, furry bee is smaller than a honeybee but very important to flower pollination in the mid-west. It visits a wide range of wildflowers native to our woodlands and prairies. As females don’t feed males the male bee must gather his own nectar and is also an important pollinator. This includes his visits to the rare, Mead’s milkweed (Asclepias meadii). The Cypripedium reginae does not give the bee any reward and traps it temporarily in its sac. Anthophora abrupta are potential pollinators of many important crops including: cranberry, tomato, blackberry, asparagus, persimmon, clover and raspberry.

7. Orchid bee - Eulaema meriana

- Geographic Distribution: New world tropics.

- Nest Characteristics: Ranging from small single-female nests to large nests with more than one female and a possible division of labor. Mud is the preferred building material with a little resin from wounded trees. Each female constructs 8 brood cells rearing her larvae on the pollen and nectar of many tropical trees, bushes and orchids.

- Habitat: Tropics

- Size: Large

- Identification: Big, hairy and velvety with exceptionally long tongues. Black head and thorax with black and yellow striped abdomen. Hair coloration at the back end, around the stinger burnt orange. Wings are yellow translucent with veins.

- Other: Male bees collect fragrance from plants to attract females, in turn pollinating them.

There are about 25 species in the genus Eulaema through the New World tropics. They are big, hairy and velvety insects unlike their smaller, shiny, metallic cousins, the blue and gold and violet colored orchid bees (Euglossa species). Two to four pregnant females of Eulaema meriana share the same nest but do not really cooperate with each other. They come to collect the spicy perfumes of the flower. A male E. meriana needs to make his own personal cologne to complete his life-cycle. Therefore, if a male of E. meriana visits a vanilla flower it may not be looking for nectar at all but something to add to its cache of perfume. Male bees are territorial and have a specific perch where they will wait for an attracted female.

Resources

Web Resources

North American Orchid Conservation Center

Native Orchid Conference, Inc.

International Journal of Agriculture and Biology

Andrews Forest – Oregon State University

University of Michigan – Museum of Zoology

University of Florida - Featured Creatures

University of Manitoba – Department of Entomology

North Carolina Native Plant Society

Videos

- Drunk wasp falls off of Epipactis purpurata

- Insects pollinating orchids in Europe

- Hand pollinating a vanilla orchid

Text Resources

- Be sure to keep an eye out for Dr. Bernhardt and Dr. Meier’s upcoming book titled: Darwin’s Orchids: Then and Now – coming to shelves this summer!

- Argue, C.L. 2011. The Pollination Biology of North American Orchids: Volume 1: North of Florida and Mexico. Springer Science and Business Media. Bernhardt, P. & Edens-Meier, R. 2010. What we think we know vs. what we need to know about orchid pollination and conservation: Cypripedium L. as a model lineage. Botanical Review 76: 204-219

- Bernhardt, P. 2002. The Rose’s Kiss: A Natural History of Flowers. University of Chicago Press China.

- Bernhardt, P. 2003. Wily Violets & Underground Orchids: Revelations of A Botanist. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. .

- Brown, P. M., C. Smith and J. S. Shriver. 2008. A new fringed Platanthera (Orchidaceae) from the Central Appalachian Mountains of Eastern North America. North American Native Orchid Journal 14(4): 239-253.

- Dixon, K. W., S. P. Kell, R. L. Barrett & P. J. Cribb (editors). 2003. Orchid Conservation. Natural History Publications, Kota Kinabalu, Sabah.

- Dressler, R.L. 1993. Phylogeny and Classification of the Orchid Family. Dioscorides Press (an imprint of Timber Press), Portland, Oregon. Edens-Meier, R., Arduser, M., Westhus, E. & Bernhardt, 2011. Pollination ecology of Cypripedium reginae Walter (Orchidaceae): Size Matters. Telopea 13: 327-340. *** This has good color photos of the flower and its pollinator.

- Edens-Meier, R.M., Vance, N. Luo, Y.B., Li, Peng, Westhus, E. & Bernhardt, P. 2010. Pollen-Pistil interactions in North American and Chinese Cypripedium L. (Orchidaceae). International Journal of Plant Sciences 17: 370-381.

- Kindlmann, P., J. H. Willems & D. F. Whigham. 2002. Trends and Fluctuations and Underlying Mechanisms in Terrestrial Orchid Populations. Backhuys Publishers, Leiden.

- Krupnick, Gary A., McCormick, Melissa K., Mirenda, Thomas and Whigham, Dennis F. 2013. The status and future of orchid conservation in North America. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden, 99(2): 180-198. http://dx.doi.org/10.3417/2011108

- Li, P., Luo, Y., Bernhardt, P., Kou, Y., Perner, H. 2008. Pollination of Cypripedium plectrochilum (Orchidaceae) by Lasioglossum spp. (Halictidae): the roles of generalist attractants versus restrictive floral architecture. Plant Biology 10: 220-230.

- Li, P., Luo, Y.B., Bernhardt, P., Yang, X.Q. & Kou, Y. 2006. Deceptive pollination of the lady’s slipper Cypripedium tibeticum (Orchidaceae). Plant Systematics & Evolution 262: 53-2006.

- Lipow, S.R., Bernhardt, P. & Vance, N. 2002. Comparative rates of pollination and fruit set in widely separated populations of a rare orchid (Cypripedium fasciculatum). International Journal of Plant Science. 163: 775-782.

- Luer, C.A. 1972. The Native Orchids of Florida. The New York Botanical Garden. Bronx, New York. Luer, C.A. 1975. The Native Orchids of the United States and Canada: Excluding Florida. New York Botanical Garden. Bronx, New York. Micheneau, C., Johnson, S.D. & Fay, M.F. 2009. Orchid pollination; from Darwin to the present day. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 1-19. Siegl, C. 2011. Orchids and Hummingbirds: Sex in the fast lane. Orchid Digest, Jan., Feb. Pp 8-17. Stewart, S. L. & A. Hicks. 2010. Propagation and conservation status of the native orchids of the United States (including selected possessions), Canada, St. Pierre et Miquelon, and Greenland. N. Amer. Native Orchid J. 16: 47–66.

- Swarts, N. D. & K. W. Dixon. 2009. Terrestrial orchid conservation in the age of extinction. Ann. Bot. 104: 543–556.

- Van der Cingel, Nelis. An Atlas Of Orchid Pollination: America, Africa Asia, And Australia. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkeman. 2001. Waterman, R. J. & M. I. Bidartondo. 2008. Deception above, deception below: Linking pollination and mycorrhizal biology of orchids. J. Exp. Bot. 59: 1085–1096.

Credits

This webpage was made possible with the help and advice of many people. We especially want to thank the following people for their much appreciated input!

Scientific Advisors and Writers

Dr. Peter Bernhardt is professor of biology at Saint Louis University and a research associate at the Missouri Botanical Garden and the Botanic Garden and Domain Trust in Sydney, Australia. He is the author of many books, including, most recently, Gods and Goddesses in the Garden: Greco-Roman Mythology and the Scientific Names of Plants.

Dr. David Inouye is a Professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Maryland, College Park. David is on the Steering Committee of the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign, on the Board of Directors of the National Phenology Network, and the Scientific Advisory Board of the Endangered Species Coalition.

Gary Krupnick is the head of the Plant Conservation Unit in the Department of Botany, National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. His research examines how data from herbarium specimens can be used in assessing the conservation status of plant species.

Dr. Retha Meier is associate professor in the College of Education and Public Service at Saint Louis University and a research associate with the Missouri Botanical Garden in St. Louis and the Kings Park and Botanic Garden in Perth, Western Australia. She is an authority on pollination ecology and plant breeding systems who specializes in rare and endangered plant species.

Poster Artist

Emily Underwood is a scientific illustrator living and working in central California. Her work is inspired by the landscapes that surround her and everything that lives and grows on them. She creates art to convey her enthusiasm for the natural world. She recently completed the Scientific Illustration program at California State University, Monterey Bay. She earned a M.S. in Geology from Oregon State University and a B.S. in Earth Science from U.C. Santa Cruz.

Photograph Providers

- Sam Droege

- Steven Falk

- David Inouye

- Verne Lehmberg

- Maria Mantas

- Gary McDonald

- North American Orchid Conservation Center

- Laurence Packer Ph.D.

- Ian Shackleford

- Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute

- Nan Vance

- H. Zell

- William Vann